Fri, 20 Aug 2004

My Interview with the Internet Monk

Two months ago Camassia brought Michael Spencer (a.k.a. The Internet Monk) to my attention when she e-mailed me a link to this article on how Christians can not ruin their children. I e-mailed Spencer with my thanks for the article. (Please don't take that as either an admission or a denial that I'm ruining my children.)

Some time later I was delighted to get an invitation from Spencer to answer an interview of twenty terrific questions about evangelicalism, Pentecostalism, and other good things. I accepted it, and the results are now here on his site in "Telford Work: The Internet Monk Interview."

Many thanks to Spencer, and also to Camassia for getting us in touch. And now, like every good Pentecostal, I'm off to synagogue!

18:05 (file under /topics/publishing)

Finally

Is it just me, or is this year's Olympics coverage actually decent?

15:43 (file under /topics/general)

Failures of Tribal Intelligence

Related to yesterday's ramble, and pressing home its point: this morning's news surfing turned up the most convincing explanation I've heard so far for Kerry's Cambodia troubles – one which if true basically exonerates Kerry:

In this case, the mistake on a detail tends to support everything else: he confused OUR holiday [Christmas], with theirs [Tet] – and over 30 years of telling the tale, he's gotten the handle wrong.

Even if this weren't the definitive explanation, it would still be a better way for the campaign to defuse the SwiftVets' bomb than anything it has done so far. So why aren't they using it? And why aren't the news media who are finally getting around to publicizing the issue testing this hypothesis?

Probably because they don't know about it. After all, it came from outside the tribe – from a reader's e-mail to Virginia Postrel, a libertarian who lives in Los Angeles.

From those humble origins the meme has been slowly working its way through the comments sections of related posts on other people's sites. In another day or two perhaps Glenn Reynolds will feature it and help shift the Internet debate. Unfortunately for the Kerry campaign, Kerry's people have already spun themselves too far towards incompatible and unpersuasive explanations to exploit it nearly as effectively as they could have.

This e-mailer's little insight could have really helped the campaign. It fits the mainstream media's generally pro-Kerry agenda. What is keeping it obscure is not "liberal bias," but the media-tribe's cocoon.

Why didn't all those intelligence agents and investigators connect the dots and see 9/11 coming? For similar reasons: disregard for outsiders, predisposition to seeing things a certain way, weak intelligence, and lack of coordination. They had made themselves structurally unable to see and act on it.

I don't know what I would do if I were in charge of an intelligence agency, but if I were a newspaper editor, I would employ a couple of interns whose whole job would be to scan weblogs and other materials from beyond the tribe looking for leads and learning about the communities those leads might come from. Then I would circulate their findings and air the most promising ones in my staff meetings.

I'm not a newspaper editor. But I am a teacher in the evangelical Christian tradition, where the dynamics can be similar. Some of us (especially fundamentalists) are huddlers: everything we learn is filtered for us by insiders. Some of us (especially missionaries) are travellers: we go outside the tribe to see for ourselves. Both approaches have their hazards and their benefits. Huddlers gain a depth and coherence of vision, while travellers gain breadth and freshness from seeing works of the Spirit they could not have anticipated.

We need to huddle and travel. In liturgical terms, we need to gather and go. We also need church offices to oversee, refine, and mentor both those activities. We need a higher regard for outsiders, openness to different ways of seeing, better intelligence, and tighter coordination.

Failure to huddle, to travel, or to connect the two will ultimately leave Christians either cocooned or dissolved – or perhaps cocooned then dissolved, as may be happening to the tribe whose oligopoly on information in America is eroding with every new failure of intelligence.

Success will not only serve the tribe and the tribes beyond it, but might just convert the tribes into something better: a fellowship that transcends the old boundaries.

Now in Christ Jesus you who were once far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. For he is our peace, who has made us both one, and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility, by abolishing in his flesh the law of commandments and ordinances, that he might create in himself one new human being in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us both to God in one body through the cross, thereby bringing the hostility to an end. And he came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near; for through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father. So then you are no longer strangers and sojourners, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God ... (Eph. 2:13-19).

Shabbat shalom.

14:27 (file under /topics/method)

Thu, 19 Aug 2004

Media Credibility after Objectivity

I've been following with interest the mainly conservative-libertarian, and now broader, discussion of the "self-destruction" of media credibility during this campaign. You will see below why I care so much about this; as usual, it's theological.

I have appreciated Roger Simon's remarks. Now, in Tech Central Station (via InstaPundit), Frederick Turner traces it back:

This collective view emerged as a rather well-intentioned product of an age of wild hope, ill-informed academic speculation, and youthful optimism about the world. Nurtured in the great European and American universities, it was statist, existentialist, anti-religious, suspicious of any science that did not support its views, snobbish, pacifist, anti-technological, hedonistic in practice, puritan in theory, postmodernist in its tastes, committed to a social rather than an individual morality, hostile to the virtue tradition, sentimentally Romanticist in its attitude to Nature (which, in an unconsciously Creationist turn, did not include human beings), relativist about cultural differences, legalistic, optimistic about human nature, and deeply hostile to the marketplace. In one sense it was a nostalgia for the aristocratic European world of our collective rose-tinted memory, when the virtues of artists and intellectuals and university-educated people were recognized automatically, and merchants and financiers were "rightly" despised. In another sense it was a yearning for the dear lost days of revolutionary fervor, moral certainty, "free" sex and callow cynicism about tradition and respectability. It was escapist in its worship of Otherness – cultural, social, political, economic, ideological, sexual, biological – and conformist in its anxious attention to the next move of its "coolest" current leadership.

Whew! The whole article has this kind of Destructive Generation feel to it, which will wreck its plausibility outside the circles that already share Turner's views. That's too bad, because aside from the melodrama his argument comes down to a much more supportable contention:

The problem is that with the collusion of their editors the new generation of reporters chose to use their exalted position of trust in the Fourth Estate to prosecute their political ambitions, rather than – as had the conservative talk show hosts – doing it the hard way, by creating a soap box of their own and building a popular audience. Their anthropology and history and literary theory classes had taught them that every system of knowledge was just the servant arm of the regnant regime of power, and that therefore no respect need be given to institutions of so-called objectivity and research balance. Editorializing crept into the news pages and then right out onto the front page above the fold.

Now I think every system of knowledge is the servant arm of a regnant regime of power, and I also think objectivity and balance are philosophically indefensible goals. This is not because I belong to the culture Turner describes in the first paragraph I cited. Systems of knowledge are powers and principalities because of human depravity, the noetic effects of sin, and the reality of structural sin. Objectivity is an illusion because of the irreducible subjectivity of the world, which is a consequence of the interrelatedness of God and creation. Balance is a Hegelian notion, not a Christian one; a balance of wisdom and folly is just folly.

So why am I sympathetic to the journalists' critics in this discussion?

Every literary genre comes with conventions and expectations: documentary, reporting, commentary, preaching, etc. Journalistic conviction and practice are increasingly incompatible with the conventions and expectations of its traditional genres.

The problem is that editors and reporters are letting go of their old (false) notions of objectivity and balance without properly embracing the virtues of trust, fairness, honesty, and humility that are proper to these genre of news reporting, and which keep subjectivity and conviction from metastasizing into dominance and arrogance.

Affirmation of these virtues may be hard to find in some classes and some schools, but it is certainly not absent in anthropology/sociology, history, or literary theory. (We offer it in theology too, if contrite journalists get desperate.)

I do not know exactly what is going on in contemporary journalism. But I do know that for whatever reason, mainstream journalists seem to be massively failing to appreciate both that our trust of them is slipping away, and on what that trust was and might again be based.

The unfolding disaster reminds me of the loss of credibility of clergy – particularly (and somewhat unfairly) Catholic clergy in the last few years. Priests weren't trusted because they are objective or balanced; they were trusted because they were good. They were grounded in a common tradition with their parishioners that was beneficial, visible, and somewhat appreciable even to outsiders. Violating the conventions of that tradition, not just in abuse but especially in responding to abuse of their own people, is what has cost them so dearly.

Like clergy, mainstream journalists also represent some social circles much better than others. They are partisan, in the general rather than formally political sense of that word. Such overrepresentation is not an optimal situation, but it is okay as long as members of the dominant group do their best to compensate. But failing to compensate (for instance, by dismissing rather than struggling really to understand and accurately represent outsiders) has greatly weakened journalists' standing.

Isolation and partisanship had already cost mainstream journalism the support of other tribes. These have created their own journalistic communities in response (some of whom have the same problems (cough – Fox News – cough). Now their own tribe members are suffering too (as Los Angeles Times readers suffered in November by being totally out of touch with the dynamics of the gubernatorial recall). The problem is thus reaching a new and critical stage.

My hope is that the disconnect between journalists and their own fellow tribesmen won't be as bad as the disconnects outside their tribe, and that this will put them in a better place to sense and correct the problem.

My fear is that a few "journalistic fundamentalists" will misdirect the salvage operation by trying to turn back to notions of objectivity and balance. That is not going to solve the problem, because those notions are both wrong and less and less intelligible to either journalists or their publics.

But trust, fairness, honesty, and humility are not. Postmoderns can earn and receive respect from both social insiders and social outsiders, just as premoderns could. Respect doesn't rest on fidelity to Enlightenment ideals, but on virtues and practices that maintain all human communities (and that come to judgment, redemption, and perfection in the Kingdom of God).

I don't really worry about chaos ensuing when the only press left in America is a partisan press and everyone knows it. Because we depend on virtuous practices and leaders to live, responsible and well respected people and institutions will fill the vacuums opening up as journalists, clergy, academics, and others fall from grace.

Perhaps the Internet, which has been such a force in speeding popular disillusionment with mainstream journalism, will be a primary medium for them. Who knows? There is no predicting the results of emergence out of instability.

I do know, however, that the virtuous – the good, the fair, the honest, and the humble – are in a much better position to emerge. And I think journalistic institutions are capable of being places that support and strengthen these virtues.

Consider how Esau lost his birthright. That's what the mainstream media are doing this year.

Then consider how Joseph, Daniel, and Esther win the respect of the powers inside and outside their tribe, and how Jesus will make his reign known to the ends of the earth. This is just basic Christian eschatology:

Beloved, I beseech you as aliens and exiles to abstain from the passions of the flesh that wage war against your soul. Maintain good conduct among the Gentiles, so that in case they speak against you as wrongdoers, they may see your good deeds and glorify God on the day of visitation. ... For it is God's will that by doing right you should put to silence the ignorance of foolish people. ...

Do not return evil for evil or reviling for reviling; but on the contrary bless, for to this you have been called, that you may obtain a blessing. For "He that would love life and see good days, let him keep his tongue from evil and his lips from speaking guile; let him turn away from evil and do right; let him seek peace and pursue it. ... Always be prepared to make a defense to any one who calls you to account for the hope that is in you, yet do it with gentleness and reverence; and keep your conscience clear, so that, when you are abused, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame. For it is better to suffer for doing right, if that should be God's will, than for doing wrong. For Christ also died for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God... (1 Pet. 2:11-15, 3:9-18).

14:38 (file under /topics/method)

Mon, 16 Aug 2004

A Biblical Worldview? No Thanks

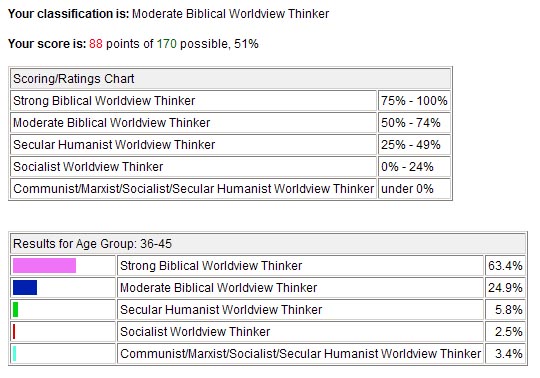

Joe Carter at the evangelical outpost has a helpful criticism of the "biblical worldview test" (and marketing device) from the folks at "Worldview Weekend".

Carter quotes Jack Heller, an evangelical professor who got a higher score as a fictitious conservative non-believer than as himself (read the whole thing, it's marvelous), then concludes that "the makers of the test appear to confuse having a 'moderate biblical worldview' with having a 'moderate Republican worldview.'" Yep (except that that condemnation gives 'Republican' a bad name). Still, I prefer Heller's own conclusion:

If a person can deny the resurrection of Christ and still appear to have a Christian worldview, if a Christian in Asia could not take a Christian worldview test and pass it, then these tests are not a valid assessment of whether a person has a Christian worldview. The tests may assess how well an American agrees with the religious right, but if that is their purpose, then it is deceptive to call them Christian worldview tests. I cannot imagine the previous generation of thinkers about worldview – people such as Carl Henry, James Sire, Arthur Holmes, Francis Schaeffer – approving of these tests. As the tests idolize politics, what is cause for concern is how many significant evangelical leaders, people who really should know better, are associated with them. The point of my criticisms is not to help refine the tests. ... To suggest that all that would be needed is a statement rewritten to include the resurrection of the body would not address the assumptions underlying the structural flaw of these tests. It is quite impossible to create a test for the Christian worldview.

My own criticisms go in a different and more radical direction.

The test questions are a mishmash of canards of federalism, American political mythology, fundamentalist litmus tests, and au courant conservative causes. It is not a random conflagration, however. In fact, it nicely illustrates how American evangelicals have taken to using the term "biblical" to refer not to things the term meant for most of the Christian or even the Protestant era, but to something much more specific: what Ann Monroe called "something vaguer – a mutually accepted amalgam of teaching, culture, and instinct that they call biblical faith." (The Word: Imagining the Gospel in Modern America, p. 117.)

Incidentally, even though I have a high view of Scripture, an orthodox theology, and rather conservative politics, I am still not all that 'biblical' according to the popular criteria, as my score on the test illustrates:

Am I jealous? Not even. Worried? Yes, but not the way the people at Worldview Weekend want me to be.

The dominance of this cultural amalgam in evangelicalism marks the extent to which evangelicalism is not only a term of sociological self-identification or convenience, but an actual tradition, as well as a "Christian subculture." Now a coherent subculture and a transformed wider culture are things many evangelicals work very hard for. But the existence and popularity of a tradition whose authorities equate commitment to federalism, philosophical foundationalism, anti-evolution, etc. with commitment to Jesus Christ makes me think we need to be a lot more demanding about the subculture we want to create. The definite article in Worldview Weekend's "the Christian worldview" is hazardous, but so is the indefinite article in the often-heard phrase "a Christian culture" or "a biblical worldview." In different ways, both constructions leave the goals too amorphous – too simultaneously underdetermined and overdetermined – for their own good.

It is not that these other things are all bad; hey, I'm a federalist. It is not that a synthetic Christian culture is necessarily a bad thing; the absence of one would be perilous, and the right one could be an exceedingly good thing. However, many evangelicals' habit of driving these particular strands together and wrapping them up tightly as "biblical" is a combination of naivete, laziness, disingenuousness, manipulation, narcissism, sloppiness, and intolerance.

I really mean these words to be as strong as they are.

Heller is right that worldview-testing is futile. But the underlying confusion is in the tradition, not just the instrument. There are so many mistakes just in the assumptions of the test questions, which match mistakes in the assumptions of the tradition, that it is impossible even to know where to start unraveling the mess, let alone correcting them.

That's why I recommend the following alternative strategy to improving "the evangelical biblical worldview":

First, I call for a moratorium on evangelical use of the word "worldview." The more I hear us using the term, the more I dislike it. There is way too much nineteenth century German idealism in it. Weltenschauung was bad to begin with, and we're only making it worse.

I would suggest "paradigm" as a substitute if I were not so afraid that we would ruin it.

Second, let's make Church history a requirement for Christian cultural literacy. (Note: the history of the Church does not leap from the first century to the sixteenth or twentieth, nor from the Middle East to Britain's colonies in America.)

Third, anyone want to sponsor Monday-through-Friday seminars for Worldview Weekend staffers where they study the Bible and worship with Christian leaders from other countries?

That's just for starters.

Fortunately, it can be just for starters. There are a lot of healthy and realistic steps we evangelicals can take. This is because one of the best qualities of my evangelical tradition is that it is a tradition, and a powerful one at that. Sometimes it is a pretty poor one, but its robustness is something to be grateful for – and also something to put to use in improving it.

17:58 (file under /topics/politics)

How to Win in November

I preached a shorter version of this sermon on politics yesterday at Montecito Covenant Church, and got out alive!

It's called Generosity under Pressure: How to Win in November No Matter What.

I hope you find it helpful.

10:33 (file under /topics/preaching)

Fri, 13 Aug 2004

Disseminating

I've been away, I've been busy, and I've been rather uninspired when it comes to blogging interesting things lately. We'll see whether this post continues that last trend.

A friend of mine, A.K.M. "Akma" Adam, is involved in an intriguing effort called disseminary.org. The goal is to use the web for theological education.

The Disseminary stands for an approach to education and educational materials apart from the constraints of institutional education: credits, fees, restrictive copyright limitations, grades, and other limitations. The project envisions a variety of educational resources offered at no charge, for no formal credit. Such resources may in the long run include publications, asynchronous seminar discussions (kept available in archives), chats, interviews, audio and video recordings.

We’re passionate about what Mary Hess has called “open-source” theological pedagogy (at a 2002 Wabash Center conference).

It's a great cause, and I wish them well, but it will be quite a challenge. Learners whose exposure to theology (or anything else) mainly comes from across the net have a hard time gaining a coherent picture of a tradition. In the case of theological learning, what we end up with is often a surfer-theology. (Want a German term for that: Gewirrwellenreitertheologie. I made it extra-awkward on purpose.)

Will surfer-theology become a trend not just of religious observers and seekers but even of believers, as people form habits of learning by clicking through relatively quick and shallow impressions rather than really drinking in the visions of prophets in detail? I hope not. But I won't be surprised if it does. It takes an intensive school or vocational education to force most of us to learn any discipline adequately. And that means authorities assigning lengthy material and breathing down students' necks to make sure it is being digested. How many people in our circles either have that, or would stand for it if they didn't have to?

Whatever the fate of disseminary.org, in our emerging web culture good pastors will be essential in bringing depth to a community's theological vision. This is not because they will do all the teaching or all the thinking, but because they will likely be people's only personal focal points (a) for showing a whole community one coherent Christian life and (b) for providing the accountability essential to disciplined learning.

Perhaps this suggests an opportunity for traditional bricks-and-mortar seminaries and denominational ordination tracks: to form teachers who can lead their communities' learning rather than doing the learning for them or just being one information source in the mix.

15:46 (file under /topics/method)