Fri, 11 Aug 2006

Lake Wobegon School District

As parents of elementary school-age children, we receive annual reports on their STAR ("Standardized Testing and Reporting") scores. One of today's reports came in the mail, and guess what I noticed?

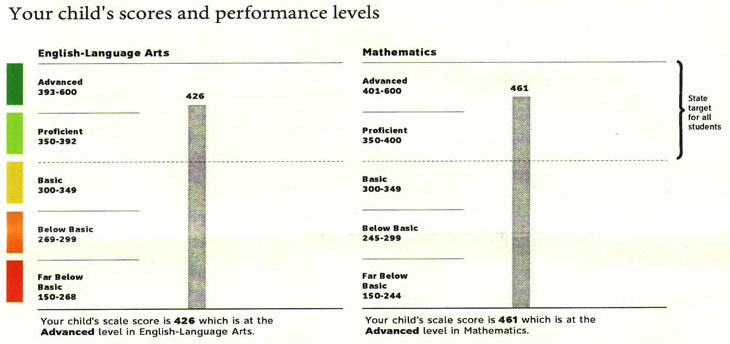

The centerpiece of the report is a graph of my child's performance compared to the state standards. Take a look:

Pretty good! However, as I studied the numbers I noticed that they aren't even 20% intervals. Every range is different from every other.

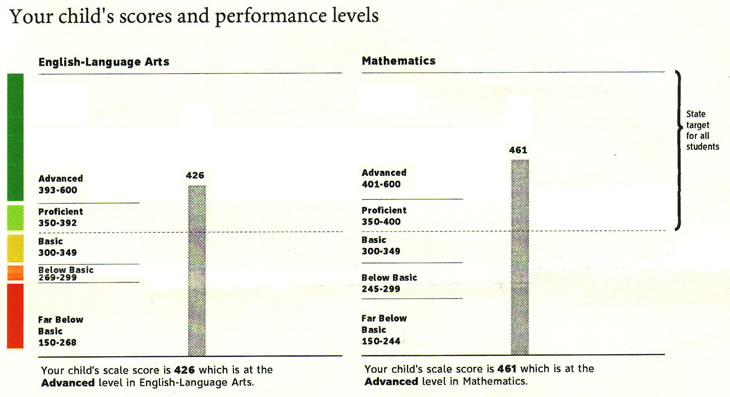

So what? So look what happens when I go into Photoshop and produce a graph where the distances are actually consistent — the way you would expect them to be on a graph:

Not nearly so impressive, is it?

Look at what happened to the dotted line. The state target just got a lot lower: 350 on a scale from 150-600 is 44% of the way up to the top, not 60% as in the first graph. Welcome to California, where below grade level is above average.

And look at what happened to my high-performing child. Still good, but not nearly as solid as it had appeared. Suddenly I see a lot more room for improvement, both on our family's part and on the part of the school. And 'Advanced' doesn't look nearly as advanced as before.

What if I had a child right between the yellow and orange levels? The report would suggest that he or she needed to do a little extra work but that things weren't that bad. Below the state's goal for our schools, to be sure — but hey, that dotted line is above the half-way point, so maybe I just have an average student and the state is being a little too ambitious. Is that how it would look if the score were only one-third of the way up the page?

This graph is by far the most prominent information on the whole page. The other side has monochrome fine print and compressed percentile statistics on components of the test, and those aren't distorted. But the image of a high-performing student and an ambitious school system is already burned into my imagination. How would I be reading them differently if I saw this first page instead?

Now the graph doesn't have to be linear to be truthful. It could use a bell curve, since the test results probably fall along one. It could use true quintiles or uneven ranges as in my Photoshopped version. But the graph isn't any of these. The total range for California STAR tests is 600-150, or 450 points. A quintile should have a range of 90 points. But the bottom (red) 'quintile' has a range of 119, or 26%. The next (orange) has a range of 31 (6%) on the left and 55 (12%) on the right. The 'middle' (yellow) has a range of 50 (11%). The penultimate (light green), corresponding to grade-level performance, has a range of 43 (9%) on the left and 51 (11%) on the right. The top (dark green), corresponding to above-grade-level performance, has by far the largest range: 208 (46%) on the left and 200 (44%) on the right.

There seems to be no rhyme or reason to the numbers, but of course there is. The chart is laid out to make the state, my school, my child, and my child's teachers all look better than they are.

Here is a larger roll-over image to help you compare the two directly.

I am a teacher too. In my circles we call this "misrepresenting the data," otherwise known as cheating.

Perhaps the ranges really need to be different. Then don't graph them! Or don't use a smooth gray bar from the bottom to where my child's scores are. Or ask the statistians that designed the testing scheme in the first place. Surely they can figure something out. But whatever you do, tell me the truth about my own child, not just in the fine print but in the headline.

My advice to California State Superintendent of Public Instruction Jack O'Connell: Next year, find someone who passed elementary school pre-algebra to do your advertising for you.

Update: I sent a link to EduWonk, who kindly responded by directing me to this article on how scores are set on these tests. I did further digging to discover that the numbers on California STAR reports are scaled but not normed, so they need not produce a normal distribution. Everything I have read indicates that those five areas are not quintiles. Graphing them as such is misleading.

21:47 (file under /topics/life)

Thu, 27 Jan 2005

A Tribute to a Teacher Under Another Name

This post is a long overdue tribute to someone.

We learn any skill through mentors and examples. I have had so many fantastic teachers through the years that the verse "to whom much is given, much will be required" truly scares me. Just about every professor I had at Fuller and Duke showed me how to be an educator, especially when they weren't trying. The names would both bore you and come across as ingratiating name-dropping. Let it suffice to say that I would be embarrassed not to single out the ones who really poured their lives into my program, and equally embarrassed not to mention every one who played even a small part, because all were significant and transformative.

The same is true of my high school teachers. Before I was old enough to learn that there were alternatives, the faculty of Flintridge Preparatory School showed me what it is to live out of the love of both learning and learners. They became my default expectation for what counts as teaching, and I have never been content not to live up to the expectations they created in me.

(What about college? Did anyone inspire me at Stanford? Sadly, no. It is not that there were not great teachers there; for instance, Stuart Reges in computer science stands out as one of the best teachers I have ever had. I think I just wasn't in an inspirable frame of mind in college. My bad.)

Still, I want to single someone out as a formative influence on my life as a teacher – precisely because he would not think to put himself on the list if I did not name him.

From tenth to twelfth grade, I was on the Flintridge varsity water polo and swim teams. I was not varsity because I was a great athlete! I was varsity because we were such a small school that there was no junior varsity. I was (and remain) a mediocre athlete.

However, we were not a mediocre team. We excelled in our league because we had an excellent coach. Brian Murphy arrived between my ninth and tenth grades and transformed my school's water polo program. In weeks he turned us into league champions. An Olympic alternate in Munich, Murph taught us the Hungarian offense and the Russian counterattack, dazzled us with stories of European superstar polo players who could tread water with air between their legs, terrified us with drills in which we had to pass the ball until it was dry, and got us in the water with morning and afternoon workouts that started at 6 a.m. and ended at 5 p.m. We even practiced on Saturdays.

Murph was intense. He shouted constantly in practices. He was more demanding in the water than any teacher in the classroom. His discipline was rigorous, his authority absolute. During games, however, he was Zen-like. He deferred to the ref, even after bad calls. He raised his voice just once in three years of competition. He took the regular 15-2 victories as serenely as the jarring occasional close defeats. He counted on all the hours of preparation to see us through the minutes of trial.

I didn't like water polo or swimming season. I was not on the teams because I love these sports. I was on the team because my parents made me choose a sport every year of junior high and high school to make me more competitive as a college applicant. I never assimilated into athletic culture. I never wanted to go to practice. I never won a race. I never started a game.

However, I learned. I worked my ass off. (Hey, a sports story deserves a little sports jargon.) My body learned the skills and gained the conditioning I needed to pass for a player. I learned to get along with real athletes. I learned asceticism and endurance. I learned how a team works. I learned the tradition of water polo. During last summer's Olympics, there I was watching water polo on TV and teaching my children the plays.

And while I never wanted to do it, I was always quietly proud of myself. Moreover, as a senior, I received the "Most Improved Award." I still hadn't scored much that season, still hadn't started, still wasn't winning races. But I was becoming a water polo player. MIP is an odd award to win in your last year of school. But my father bursted with pride when I received it at the end-of-season banquet. Now that I am a father, I finally understand why. And I am discovering the source of the same energy he and my mom mustered to be up with me making breakfast and driving me to school to get me in the water by 6:00.

A banner in my school's gymnasium still chronicles our league championships: 1981, 1982, 1983. Murph owns those years.

His responsibility for those numbers on the banner is not why I am writing this post, though.

I was at my twentieth-year high school reunion last fall talking with Flintridge's new director of development when Murph came up. As I reminisced, it hit me that Murph taught me as much about teaching as any "teacher."

My classroom is a swimming pool where people are trained and transformed rather than merely informed. My expectations are sky-high. My A and B students are learning what it is to be stretched, and my C and D students are learning what it is to persevere. We're a team. Both the non-believers, Catholics, liberal Protestants, etc. who assume they won't "belong" and the conservative evangelicals who assume they have the inside track are learning the unfamiliar hospitality and friendship of the apostles' fellowship. The books and lectures aren't ends in themselves, but leverage for playing a game worthy of the name "Christian faith." People who think of a semester as a couple of tests and a thrown-together paper are struggling to get through the regular scrimmages of nine or more written assignments, a heavy reading load of sophisticated and challenging texts, and exams without a review sheet.

As a result they are learning that Christianity is more than just guilt and justification; it's also pain and sanctification. They are learning that it's okay to blow off steam with complaints, but not okay to corrupt the team with cynicism. They are learning that the ultimate criteria of faithfulness are not how skilled or talented or insightful a player is, but whether she cheats or plays by the rules, whether she gives up or keeps going even when she's discouraged.

And my students rise to the occasion. When I put them through more than I sometimes feel I have a right to, and much more than I ever tolerated as an undergraduate, they receive it with gratitude and grow it into character that brings tears to my eyes.

One semester a few years ago my students started calling me "Coach." That floored me. I consider it the ultimate compliment of my teaching career. It also gave me a new standard to strive for. "Doctor" respects my pedigree and "Professor" my professional position, and those are kind and appropriate gestures. But "Coach" signifies something greater – a relationship of even higher respect in our culture, a relationship that offers the passing along of the same vision that Brian Murphy gave me, against my will and despite my lack of talent, for which I am permanently grateful.

Thanks, Coach. I owe you in a big way.

09:48 (file under /topics/life)